An Australian national plastics “plan”: one plan to rule all?

23 September 2022 12:03

Gerry Nagtzaam and Steve Kourabas FACULTY OF LAW MONASH UNIVERSITY

Introduction

Plastics have become a ubiquitous part of our lives.[1] Beginning from the 20th Century, they were marketed as lightweight, cheap and available for countless uses. However, between 1950 and 2015, a total of 6.3 billion tonnes of plastic waste was produced. Only 9% was recycled, 12% incinerated, and the remaining 79% either stored in landfills or released directly into the natural environment.[2] The problem is getting worse: the World Bank estimates that the world is on a trajectory where waste generation will drastically outpace population growth by more than double by 2050.[3]

Australian regulators have responded to these challenges through increased efforts to encourage less plastic consumption via a number of "end use" programs including recycling or utilising alternative materials. These efforts have tended to be fractured and in some cases, inconsistent. This article explores the legal and regulatory responses to the issue.

The plastics problem: plastic consumption and recycling in Australia

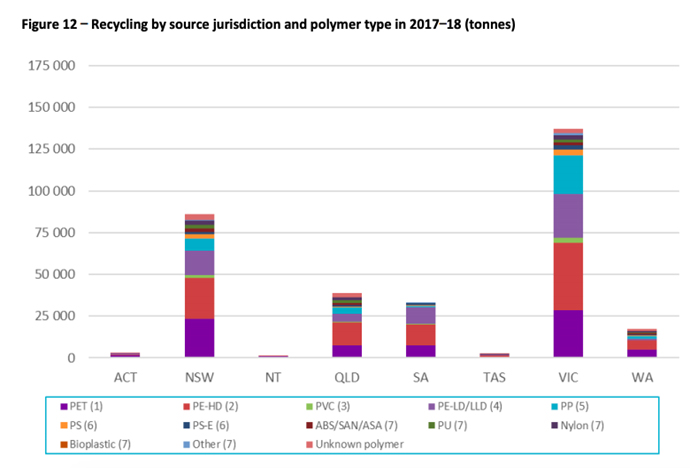

Australia produces approximately 2.5 million tonnes of plastic waste each year,[4] and approximately 130,000 tonnes of plastic leaks into the environment each year.[5] In 2017–18, the total consumption of plastics in Australia was 3,407,300 tonnes with a recovery of 320,000 tonnes, giving a recycling rate in 2017–18 of 9.4%.[6] In 2017–18, NSW consumed 1,090,000 tonnes of plastic, Victoria consumed 880,900 tonnes and Queensland 683,000 tonnes.[7] Victoria currently has the highest recycling rate at 15.6%, followed by South Australia at 14.1%.[8] The below graph breaks down by state jurisdiction of recycling and polymer type in 2017–18:[9]

A “national plastics plan”?

In 2021, the Morrison Government released its National Plastics Plan (NPP) to facilitate a unified approach to plastic use at each stage of production and consumption. The plan addresses the following:[10]

Prevention:

The NPP includes a promise to ‘work with industry to fast-track phase outs of problematic plastic materials’ by 2022.[11] The government also promised to work with state and territory governments to align disparate approaches to plastic bans.[12] [13] However, in the absence of any concrete action, a number of states and local governments implemented their own single-use plastic bans.[14]

Recycling:

The Morrison government sought to strengthen the Commonwealth Procurement Rules to make sustainability, including the use of recycled materials, part of the value-for-money assessment for everything the government buys.[15]

Most significantly, the Recycling and Waste Reduction Act 2020 (Cth) sought to regulate the export of waste material to promote environmentally sound management of waste material (including plastic).[16] The Act bans glass exports, whole new tyres, unprocessed single resin/polymer plastics, and export of mixed and unsorted paper and cardboard.[17] The export bans provide an impetus to reconfigure local infrastructure to reprocess and re-manufacture recyclables onshore and facilitate a move towards a circular economy. [18] Materials that have been re-processed and turned into other “value-added” materials can still be exported under the law.[19]

Product stewardship provisions, which require the Minister to publish a “priority list” the Minister proposes to regulate, are meant to help achieve these goals.[20] There are three approaches:

(a) voluntary product stewardship: an accreditation scheme;

(b) co-regulatory product stewardship: where companies are required to be members of co-regulatory arrangements; and

(c) mandatory product stewardship: which might require certain persons, to do, or not do, something in relation to specific products (ie restricting manufacture/import, prohibiting use of certain substances, labelling, packaging or other design elements, or reusing, recycling, recovering, treating or disposing of products).[21]

The Recycling Modernisation Fund and the Modern Manufacturing Strategy Funding, also seek to enhance recycling capacities with promises of new jobs and new recycling infrastructure (with contributions from federal, state and territory governments as well as industry groups).[22]

Consumer Education

The NPP includes a commitment for governments to work with industry to ensure all APCO members, with annual revenue greater than $500 million, use the Australasian Recycling Label by the end of 2023.[23]

To combat greenwashing,[24] the Morrison government committed to refer companies making false or misleading environmental claims to the ACCC. The government also supported the national rollout of the Recycle Mate App in 2021, which helps consumers determine whether a product can be recycled.[25] The NPP also takes aim at kerbside bin collection and container deposit schemes (CDSs) in every state and territory.

To date, these issues have been treated with differing levels of commitment by the states and territories.[26] For instance, the Victorian government committed to reform the recycling system, including provision of access to four core waste and recycling services (food and garden organics; glass; paper, plastic and metals; and residual waste).[27] The Queensland government, however, was criticised for postponing its kerbside collection services until July 2022 as part of efforts to gain revenue under the council’s 2020–21 budget. The suspension raised concerns regarding an increase in illegal dumping, which could cost the Council up to $100,000 per year.[28] In response to the criticisms, the Brisbane Council issued waste vouchers to every household, including tenants, from 1 July 2020 to help residents dispose of household items.[29]

South Australia was an early mover in establishing its CDS, introduced in 1977 to address significant volumes of beverage containers in the litter stream. The program broadly coincided with the introduction of non-refillable beverage containers such as cans and then later, plastic soft drink bottles.[30] In 2003, the scope of containers covered by CDS was expanded to include additional beverage containers prevalent in the litter stream at the time. In 2008, the refund amount was increased to 10 cents.[31] In 2017–18, almost 603 million containers were recovered by collection depots for recycling, representing a return rate of almost 77% and diverting about 42,913 tonnes from landfill or litter in that year.[32] Other states have followed the South Australian example.[33]

Protection of Ocean and Waterways

By 2019-20, the then federal government had supported over 1,330 community-led projects, totalling $18 million that address environmental problems.[34] The Environment Restoration Fund committed $100 million over 4 years to protect the environment for future generations and committed $14.08 million to remove ghost nets and marine debris pollution from strategic locations in Northern Australia.

Conclusion

Despite lofty rhetoric regarding co-ordination in the NPP, regulation of plastic in Australia continues to be sporadic, inconsistent and incomplete. States and territories take their own approaches with varying degrees of commitment and success.[35]

This runs contrary to the NPP’s endorsement of the CSIRO’s National Circular Economy Roadmap for Plastics, Glass, Paper and Tyres: Pathways for Unlocking Future Growth Opportunities for Australia (the Roadmap). The Roadmap is intended to act as a way for governments, industry and researchers to inform future decisions on investment, policy developments and research priorities.[36]

In light of the piecemeal approach, it is not surprising that efforts such as the NPP continue to receive a mix of reactions. Conservation groups have warned that the largely voluntary packaging and recycling targets must be mandated.[37] So far, the new Albanese government has not made any strong commitments regarding plastic pollution. The government has, however, emphasised the need to promote a circular economy,[38] and the Prime Minister signalled his intention to remedy perceived problems with the previous government’s policy in the following terms:

We will pick up the delayed and missing pieces in the National Waste Policy Action Plan, work with industry to improve arrangements for key materials like plastics and packaging, and lead collaboration with local, State, and Territory governments to make greater progress in standardising high-quality kerbside collection, phasing out harmful single-use plastics, and harmonising state-based container deposit schemes.[39]

It remains to be seen whether such pronouncement amount to more than vague promises.

| Gerry Nagtzaam Associate Professor |  | Steve Kourabas Senior Lecturer |

[1] The definition of “plastics” covers a myriad of synthetic polymers that are mostly derived from fossil fuel, with the addition of chemical components (although there are also bio-based materials. R C Thompson, S H Swan, C J Moore and F vom Saal, “Our Plastic Age”, (2009) Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B Biological Sciences 364 (1526), Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society 1973–76 at 1974. Many of these additives are considered potentially toxic and can be released into the environment via the development stage or as discarded waste (eg phthalates, bisphenol A (BPA), bromine flame retardants, ultra-violet (UV) screens and anti-microbial agents). In many cases, these additives have been shown to have negative effects on the biosphere and individual organic life. See, for example, A A Koelmans, T Besseling and E M Foekema “Leaching of Plastic Additives to Marine Organisms”, (2014) 187 Environmental Pollution 49; H Bouwmeeste, P Hollman and R Peters, “Potential Health Impact of Environmentally Released Micro- and Nanoplastics in the Human Food Production Chain: Experiences from Nanotoxicology”, (2015) 49 Environmental Science and Technology 8932.

[2] C J Rhodes “Plastic Pollution and Potential Solutions” Science Progress (2018) 101, No 3.

[3] World Bank, What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050.

[4] Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, National Plastics Plan 2021 (2021), 4.

[5] Above.

[6] K O’Farrell, 2017–18 Australian Plastics Recycling Survey: National Report, 1–3, 17, 42.

[7] Above 37.

[8] Above 40. Victoria’s relatively positive recycling record needs to be understood in the context that it has a disproportionately large manufacturing sector.

[9] Above 38.

[10] National Plastics Plan, above n 4.

[11] National Plastics Plan, above n 4, 5.

[12] National Plastic Plan, above n 4, 5.

[13] See for example, Environment Protection Amendment Act (Vic) 2019; Plastic Shopping Bags (Waste Avoidance) Act (SA) 2008; Environmental Protection Amendment (Banning Plastic Bags and Other Things) Bill (WA) 2018; Environment Protection (Beverage Containers and Plastic Bags) Act (NT) 2011; Plastic Shopping Bags Ban Act (ACT) 2010; Plastic Shopping Bags Ban Act (Tas) 2013. From 1 July 2018, the Queensland Government banned lightweight plastic shopping bags less than 35 microns thick, Waste Reduction and Recycling Amendment Act (Qld) 2017. The Queensland Government is planning on introducing legislation in July 2021 to ban the supply of specific plastic products including heavyweight plastic shopping bags: Lisa Cox “Queensland Moves to Ban Single-use Plastic Straws and Plates in Bid to Save Marine Life” The Guardian (15 July 2020). NSW has not enacted a plastic bag ban. Lisa Visentin, “NSW Government to Block Labor’s ‘Ban the Bag’ Bill In Favour of Discussion Paper” Sydney Morning Herald, 2 October 2019.

[14] For example, South Australia became the first state in Australia to ban plastic straws, cutlery, and drink stirrers with the Single-use and Other Plastic Products (Waste Avoidance) Act 2020 (SA), followed by Queensland’s Waste Reduction and Recycling (Plastic Items) Amendment Act 2021, then the ACT’s Plastic Reduction Act 2021(ACT). Other jurisdictions are progressing similar policies. Hobart will ban single-use plastics from 2021, becoming the first city in Australia to do so. Lucy MacDonald, “Hobart Set to Ditch Single-use Plastic, But How Will It Play Out?” ABC News 11 March 2020.

[15] National Plastic Plan, above n 4, 6. See also: Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Recycling – Taking responsibility for our plastics.

[16]RWR Act ss 1 and 2. The legislation also incorporates the Product Stewardship Act 2011 (Cth) with improvements to encourage companies to take more responsibility for their waste through various initiatives such as better product design, and increased recovery and reuse of waste materials.

[17] M Foley, “Jail Time and Big Fines: Parliament to Debate Waste Management Reforms” The Sydney Morning Herald (26 August 2020). Problematically, it is unclear how this Act interacts with the Hazardous Waste (Regulation of Exports and Imports) Act 1989 (Cth), which is the legislation that Australia uses to give effect to the Basel Convention.

[18] The RWR Act seeks to encourage and regulate the reuse, remanufacture, recycling and recovery of products, waste from products and waste material in an environmentally sound way. The Act seeks to encourage and regulate manufacturers, importers, distributors, designers and other persons to take responsibility for products, including by taking action that relates to reducing or avoiding generating waste through improvements in product design; and improving the durability, reparability and reusability of products; and managing products throughout their life cycle. RWR Act, s 3(2).

[19] J Downes, D Giurco and R Read, “‘Australia’s Waste Export Ban Becomes Law, But the Crisis is Far From Over” The Conversation (15 December 2020).

[20] The priority list for 2020 includes as the highest priority plastic microbeads and products containing them and plastic oil containers. Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, Water and Environment, 2020–21 Product List, www.environment.gov.au/protection/waste/product-stewardship/products-schemes/product-list-2020-21 .

[21] These arrangements are set out in Ch 3 of the RWR Act.

[22] National Plastics Plan, above n 4, 6.

[23] National Plastics Plan, above n 4, 8.

[24] Greenwashing are “activities by a company or an organization that are intended to make people think that it is concerned about the environment, even if its real business actually harms the environment”: Oxford Dictionary, oxfordlearnersdictionary.com.

[26] At its core, the concept of a “circular economy” responds to the need, in a more sustainable society, to efficiently and effectively use resources so as to provide societal value over a longer time period and with minimised environmental impact. M Brandão, D Lazarevic and G Finnveden “Introduction and Overview” in M Brandão, D Lazarevic and G Finnveden (eds) Handbook of the Circular Economy (Elgar 2020) 1.

[28] T Moore, “As Cases of Illegal Dumping Pile Up, Labor Calls for Kerbside Collection”, Brisbane Times, 10 February 2021, brisbanetimes.com.au.

[29] Brisbane City Council, “Waste Vouchers Fees and Charges”, brisbane.qld.gov.au.

[30] Environment Protection Australia, Government of South Australia, Green Industries “Single-Use Plastics and the Container Deposit Scheme” (Summary Paper, 2019).

[31] Above.

[32] At its height, the CDS return rate was 81% (in 2011–12) and is currently 76.9%. Above.

[33] For instance, the Victorian Government is planning to introduce a scheme, which adopts the best mix of approaches from other jurisdictions, with the aim of halving beverage container litter in Victoria within 10 years. Above 27.

[34] Australian Government, Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment, Research, Innovation and Data.

[35] These state-based approaches are outlined in detail in Steve Kourabas and Gerry Nagtzaam, ‘Australia’s Regulatory Approach to Plastic Pollution: Letting a Thousand (Plastic) Flowers Bloom? (2022) 39(2) Environmental and Planning Law Journal (forthcoming).

[36] Similarly, the RWR Act has as one of its core objectives “to develop a circular economy that maximises the continued use of products and waste material over their life cycle and accounts for their environmental impacts”. RWR Act, s 3(1)(c).

[37] The World Wildlife Fund Australia has, however, been more positive in its response to the NPP. It stated that the NPP’s 38 actions were a “breakthrough in tackling plastic pollution” and Boomerang Alliance director Jeff Angel said that the plan was a “substantial effort”: G Readfearn, “Polystyrene To Be Phased Out Next Year Under Australia’s Plastic Waste Plan” The Guardian 4 March 2021. While the RWR Act now authorises the government to include mandatory targets through the Product Stewardship provisions, it is unclear when these mandatory provisions will be activated and for what purpose.

[38]https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/live/2022/jul/19/environment-covid-obeid-anthony-albanese-peter-dutton-tanya-plibersek-epa-masks-labor-coalition-isolation-payments?filterKeyEvents=false&page=with:block-62d61d3c8f082dc50bc2b31a

[39] Labor, Waste and Recycling Plan, https://www.alp.org.au/policies/waste-and-recycling-plan

Related Articles

-

Thousands of measures are proposed across Australia annually, and hundreds end up being legislated, ranging from relatively minor, to wide-ranging policy that can have major social, economic, or industrial significance.

Thousands of measures are proposed across Australia annually, and hundreds end up being legislated, ranging from relatively minor, to wide-ranging policy that can have major social, economic, or industrial significance. -

If the wind of change a new Government typically carries failed to create a buzz in Australia’s new Parliament, a diverse crossbench, in both the Lower and Upper Houses, and invigorated public discourse, certainly will.

If the wind of change a new Government typically carries failed to create a buzz in Australia’s new Parliament, a diverse crossbench, in both the Lower and Upper Houses, and invigorated public discourse, certainly will. -

Those faced with leading organisations in current volatile environments clearly encounter significant challenges. Effective leaders are those who have the skills to make good decisions in an ambiguous environment, develop opportunities through innovation to gain a competitive advantage. They are highly valuable to organisations.

Those faced with leading organisations in current volatile environments clearly encounter significant challenges. Effective leaders are those who have the skills to make good decisions in an ambiguous environment, develop opportunities through innovation to gain a competitive advantage. They are highly valuable to organisations.

LexisNexis

LexisNexis