Top 5 facts you need to know about ASIC civil litigation

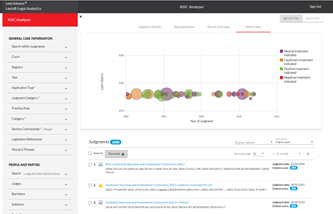

Over the last 10 years, the ASIC regulatory landscape has changed a great deal — legislative developments, funding changes, royal commissions, the political spotlight — but how does this landscape translate into real life experience in the courts? Lifting the lid on civil litigation involving ASIC — does a deeper analysis of enforcement judgments in this space reveal any surprises?

-

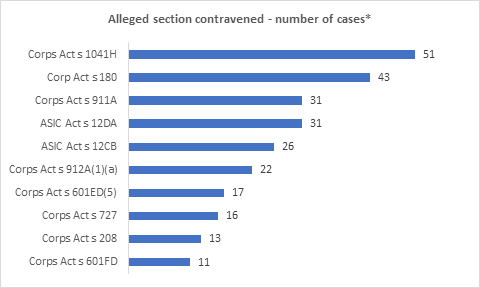

The top 10 legislative sections that lead to ASIC-led civil litigation in the Federal Court

And the winner over the last 10 years is…

Corporations Act 2001 s 1041H

Over the last decade there have been more ASIC enforcement judgments in the Federal Court revolving around misleading or deceptive conduct in relation to financial products or financial services (Corps Act s 1041H) than any other alleged type of contravention.

Second on the list - breaches by directors and other officers in exercising care and diligence in their duties (Corps Act s 180).

And coming in third - the need for an Australian Financial Services licence - litigation targeting financial services businesses that are operating without a licence (Corps Act s 911A).

Rounding out the top 5 are financial services misleading and deceptive conduct (ASIC Act s 12DA) and unconscionable conduct in connection with financial services (ASIC Act s 12CB).

The top 5 list contains a heavy weighting towards contraventions in the financial services industry and the offering of financial products. This general theme is extended when looking at the next tier of targeted provisions – including a specific focus on managed investment schemes:

- Obligations of financial services licensees to provide financial services “efficiently, honestly and fairly” (Corps Act s 912A(1)(a));

- Operating a managed investment scheme that is unregistered (Corps Act s 601ED(5));

- Offering securities without a current disclosure document (Corps Act s 727);

- Need for member approval for financial benefit in relation to public companies (Corps Act s 208); and

- Duties of officers of a responsible entity of a managed investment scheme – including requirements to act honestly, with a reasonable degree of care and diligence, to act in the best interest of members and not to gain benefit either directly or indirectly for themselves to the detriment of members etc (Corps Act s 601FD).

ASIC has made temporary changes to its priorities in order to adapt to the impact of COVID-191. Although it seems unlikely that this will impact heavily on the types of sections being targeted in the top 10 list, it will be interesting to monitor any impacts on ASIC litigation patterns in the coming years.

-

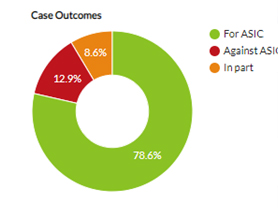

How successful has ASIC been in civil litigation?

In short – very.

Overall, ASIC have been successful, or partly successful, in 88% of civil litigation enforcement actions it undertakes in the Federal Court (including the full court) and the High Court*.

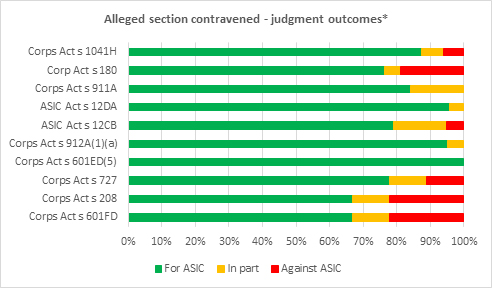

ASIC success rates* vary depending upon what section has been allegedly contravened, but of the top 10 sections most frequently targeted, the rates are high across the board – ranging from a “low” of 67% (Corps Act s 601FD; Corps Act s 208) to a high of 100% (Corps Act s 601ED(5)).

It should be noted that although statistically speaking defending an ASIC action is an uphill battle, it would be remiss in discussions to not mention exceptions. A relatively recent example - Westpac had come to the table with the acceptance of a $35 million fine in relation to alleged responsible lending breaches. Put forward to the court for 'rubber stamping', the proposed penalty agreed between the parties was rejected and the action ultimately dismissed2. So, twists and turns are always possible. But looking purely at the data, in terms of risk mitigation it would be fair to say a sounder strategy is to put in place strong compliance systems and avoid the courts in the first instance.

-

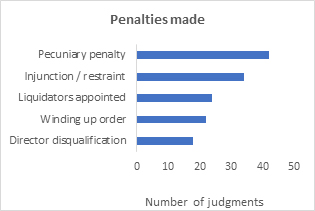

So what types of penalties have been handed down?

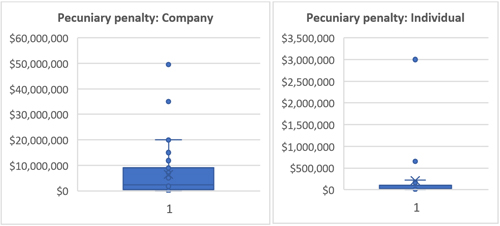

Legislative guidance on penalties is obviously of central importance – but real-life analytics assist to complete the picture. An analysis of Federal Court orders (enforcement) reveals the types and range of penalties handed down - information to provide better data-driven advice to clients or boards.

Top 5 Orders made in Federal Court judgments by volume (2011-2020)

It is not surprising that in the last 10 years the most common penalty handed down in Federal Court orders in relation to ASIC-led enforcement litigation was a pecuniary penalty. The record for the highest penalty imposed on a corporation currently stands at $49,500,0003, with the highest penalty for an individual at $3,000,0004.

Injunctions (excluding interim injunctions) were the second most common order made – ranging in duration from 7 months to permanent.

Winding up / liquidators appointed orders were made in around 24 judgments.

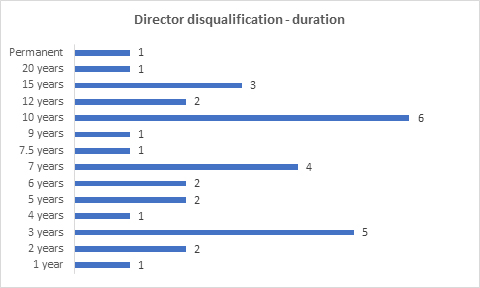

The fifth most common penalty type was a director disqualification - the period of disqualification ranging from 12 months to permanent.

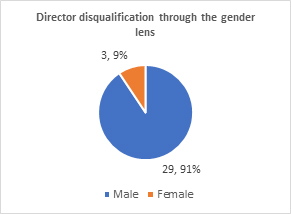

And what if we apply a gender lens on these disqualifications? (to put some context around this stat… the Australian Institute of Company Directors have recorded current female Board representation on ASX 200 companies at 31% https://aicd.companydirectors.com.au/advocacy/board-diversity)

-

Where does all the action take place?

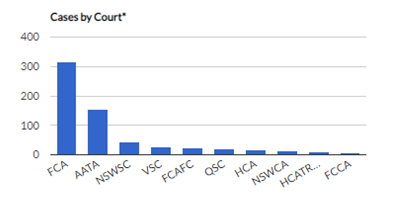

Since 2010, the majority of ASIC civil litigation has been undertaken in the Federal Court.

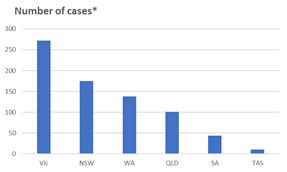

And the busiest Federal Court registry? The honour goes to Victoria, managing to trump New South Wales. This bucks the trend for litigation that we see elsewhere.

Registry breakdown by volume

Other trends of note – the increase in review activity in the Administrative Appeals tribunal and the decline in the volume of judgments involving ASIC as a party in the Supreme Courts.

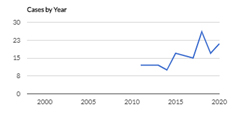

Volume trend in Administrative Appeals Tribunal post-2010

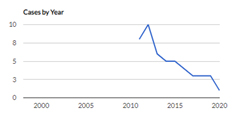

Volume trend in NSW Supreme Court post-2010

-

Ready to prepare your legal argument?

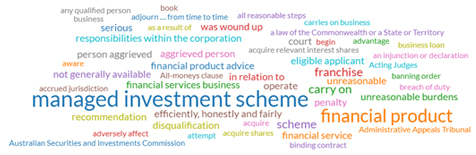

When looking at the types of words and phrases that have been judicially considered in ASIC cases, two words in particular jump out in terms of volume: “managed investment scheme” and “financial product”

This further reinforces the most targeted sections list (Ref. section 1) and reflects the weighting of litigation towards the financial services industry and financial product offerings.

And the most frequently cited cases in ASIC judgments?

A High Court case stemming from one of the biggest civil cases in the history of the NSW Supreme Court, with ASIC alleging that the executive directors of One.Tel telecommunications company had failed to meet their duties in the months leading up to the company's collapse in May 2001.

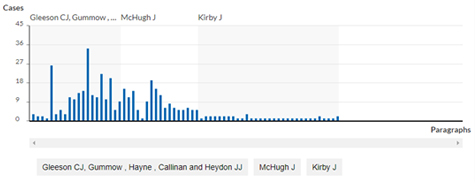

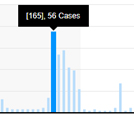

Paragraph Citation visualisation from CaseBase: Rich v ASIC

Most cited paragraph: Paragraph 32, 34 cases cite this paragraph (per Gleeson CJ, Gummow, Hayne , Callinan and Heydon JJ)

[32] Secondly, and more fundamentally, the supposed distinction between "punitive" and "protective" proceedings or orders suffers the same difficulties as attempting to classify all proceedings as either civil or criminal36.. At best, the distinction between "punitive" and "protective" is elusive. That point is readily illustrated when it is recalled that, as McColl JA pointed out37., account must be taken in sentencing a criminal offender of the need to protect society, deter both the offender and others, to exact retribution and to promote reform38.

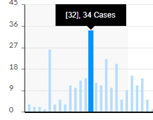

A matter around takeovers that involved the testing of ASIC powers from a constitutional perspective.

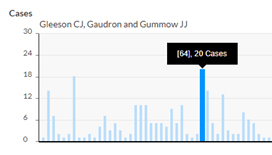

Paragraph Citation visualisation from CaseBase: ASIC v Edensor Nominees Pty Ltd

Most cited paragraph: Paragraph 64, 20 cases cite this paragraph (per Gleeson CJ, Gaudron and Gummow JJ)

[64] "Jurisdiction" and "power" are not discrete concepts. The term "inherent jurisdiction" may be used, for example in relation to the granting of stays for abuse of process, to describe what in truth is the power of a court to make orders of a particular description70. In Harris v Caladine, Toohey J said71: "The distinction between jurisdiction and power is often blurred, particularly in the context of 'inherent jurisdiction'. But the distinction may at times be important. Jurisdiction is the authority which a court has to decide the range of matters that can be litigated before it; in the exercise of that jurisdiction a court has powers expressly or impliedly conferred by the legislation governing the court and 'such powers as are incidental and necessary to the exercise of the jurisdiction or the powers so conferred'72."

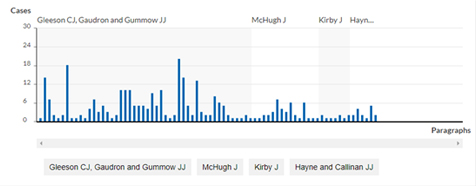

Arising from the James Hardie corporate scandal – and one of the longest running litigation matters in Australian history. A case dealing with the directors of the company and whether announcements to the market were misleading in relation to compensation funds.

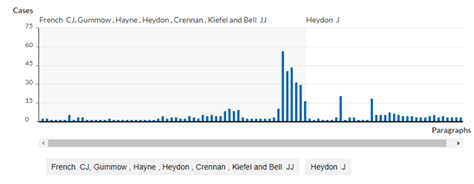

Paragraph Citation visualisation from CaseBase: ASIC v Hellicar

Most cited paragraph: Paragraph 165, 56 cases cite this paragraph (per French CJ, Gummow, Hayne, Heydon, Crennan, Kiefel and Bell JJ)

[165] Disputed questions of fact must be decided by a court according to the evidence that the parties adduce, not according to some speculation about what other evidence might possibly have been led. Principles governing the onus and standard of proof must faithfully be applied. And there are cases where demonstration that other evidence could have been, but was not, called may properly be taken to account in determining whether a party has proved its case to the requisite standard. But both the circumstances in which that may be done and the way in which the absence of evidence may be taken to account are confined by known and accepted principles which do not permit the course taken by the Court of Appeal of discounting the cogency of the evidence tendered by ASIC.

So, in summary, what does the data suggest…

Top tips - ensure you have strong compliance programs in place; tread very carefully – especially in financial services; if challenging ASIC, be aware that historical success rates are not on your side (unless you are ASIC); prepare well – and potentially prepare to pay…

Scope Statement

- The content set covers judgments where the Australian Securities & Investments Commission (“ASIC”) is identified as a party to the case

- Coverage from 1st January 2011 to 1st November 2020

- Coverage is based on cases available in LexisNexis’s CaseBase and Unreported Judgments database

- Only includes cases that have reached written judgment stage

- Includes principal judgments and judgments of a procedural nature

- The analysis for Sections 1, 2 and 3 is in relation to judgments from the Federal Court of Australia (ASIC civil enforcement focus), Federal Court Full Court, High Court of Australia and High Court of Australia (special leave transcripts)

- The analysis for Sections 4 and 5 considers ASIC-led litigation across all Courts in scope as per above

- It is acknowledged that the use of the term “success” in Section 2 is subjective in nature. For the purpose of this analysis, the following assumptions have been used:

- Outcomes are assessed for principal judgments only; outcome is assessed at a judgment level; procedural judgments are excluded from the outcome analysis

- “For ASIC” is defined as where ASIC has been successful in its application (ie one or more alleged contraventions have been established)

- “Against ASIC” where the proceeding has been dismissed

- “In part” is defined as where there are multiple respondents and one or more of the respondents have had proceedings dismissed OR if a substantial number of contraventions are not proven OR an appeal is identified as being allowed “in part”

- All statistics/assumptions are from LexisNexis’s industry-acclaimed case citator, CaseBase and ASIC Analyser

- The gender lens on director disqualification is a high-level binary analysis only. It is based on party name identified in judgment where contravention established

NOTE LexisNexis retains copyright in the form and content of this Report. The views and opinions expressed in this Report are based on certain parameters, assumptions and materials mentioned herein. LexisNexis cannot guarantee that the content of this Report is accurate and complete in all respects, and LexisNexis excludes all liability in regard to the same.

1 Interim Corporate Plan, https://asic.gov.au/about-asic/corporate-publications/asic-corporate-plan/#interim

2 AUSTRALIAN SECURITIES & INVESTMENTS COMMISSION v WESTPAC BANKING CORPORATION (2018) 132 ACSR 230; [2018] FCA 1733; BC201810662

Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Westpac Banking Corp (Liability Trial) (2019) 139 ACSR 25; [2019] FCA 1244; BC201907218

Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Westpac Banking Corp (2020) 380 ALR 262; (2020) 145 ACSR 382; [2020] FCAFC 111; BC202005844

3 Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Mitchell (No 3) [2020] FCA 1604; BC202010795

4 Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) v Gallop International Group Pty Ltd (2019) 138 ACSR 395; [2019] FCA 1514; BC201908343

Author Profiles

JULIE AUSTIN

Data Analytics Manager- Major Projects

LexisNexis® Australia

Julie has over 20 years’ experience in the legal content and technology industry. She has worked extensively with local and international teams, including Australia, New Zealand, India, USA, China and the UK. Julie’s current role focuses on applying the latest analytic technologies to a range of legal information to make information more accessible and gain new insights. Julie looks at product design from an end-to-end perspective, from content architecture through to front-end design to support a holistic user experience.

SEETA BODKE (Contributing author)

Product Manager – Legal Analytics

LexisNexis Australia

Seeta Bodke is a Product Manager in the Legal Analytics team with LexisNexis. She has been focused on developing the Lexis® Legal Analytics suite of products; identifying customer needs and staying abreast on the evolving legal IT landscape. Her experience includes working across global teams from Australia, USA, UK and India, building products in the information publishing and legal domain space and working with Engineering to develop and implement the technology.

LexisNexis

LexisNexis